Introduction

Today, most governments are focused on understanding the economic growth they rely on, and take strong measures to sustain this growth. Why are they so focused on this element? It is very clear that most governments see growth as an answer to their problems: developed countries can reduce their debt and maintain social stability, and developing countries can address their development challenges and raise social levels. This also clearly demonstrates that a zero-growth approach is just not realistic and certainly not politically feasible.

But as much as growth is an answer to these issues, it also often creates its own problems, due to unsustainable patterns such as the creation of bubbles, the overuse of natural resources and the effect on the environment. This implies that we need to better understand the future limits to growth and use this understanding to reconfigure growth in a way that is increasingly sustainable.

Reconfiguring Growth

To reconfigure growth, we need to look in depth at the challenges and limits. Furthermore, it is also clear that only these facts - that are commonly agreed and shared - can be a real basis for change. Otherwise, we will not see the limits to growth and we will be like someone driving at 200 km/h towards a wall; not yet seen but which is just around the corner.

Before looking in depth at these limits to growth, we need a better understanding of basic human nature and behavior, which adds to the challenges for this reconfigured growth.

First, we need to understand that we humans have trouble in dealing rationally with limited commons. To illustrate this, consider the Swiss concept of commons. In the past, when Switzerland was essentially a rural society, each village had a pasture that belonged to the whole community. Farmers could use this common pasture for grazing their cows. It was clearly attractive for every farmer to own a cow, as his animals had access to this common pasture, and hence there was no visible limit to the amount of grazing land for his cows. For a farmer, the downside was the cows of all the other farmers in the community grazing the same common pasture. Since every farmer thought the same, the pasture became over-grazed and there was no grazing left. What does this teach us? If we are given access to a common good, we will very naturally continue to increase our own use of it, as we cannot immediately see or feel the negative effect. Hence, we will not work rationally in this case, even if we might have understood the issue intellectually. And so the only conclusion possible is that we will eventually over-use a common resource and eventually destroy it. And there are actually only two possible solutions: either enforce strict rules of use or privatize the common resource. But now there is another solution, a variation on the first two: if everyone calculates the future loss and negative effect on themselves and includes it in their economic balance, then the issue will be solved.

Second, we have an almost unstoppable belief that technology will be our ultimate savior. But we have already learned (even if we very often forget) that technology alone - without a fundamental change in societal behaviour and rules - will not have the desired effect. Let me give you an example regarding the use of private cars. The availability of alternative forms of transport, that have less effect on the environment, will not change our approach to mobility. However, if societal behaviour and rules adapt - for example, if there is less parking making the use of a car very complicated or there are higher taxes for private cars with higher CO2 emissions - then we will comply and the change will happen at the necessary speed.

Limits to Growth

Having briefly defined the framework and the background to this discussion on the limits to growth, I will now present the very important and often overlooked limits to growth: first, the effect of resource use and scarcity on the competitiveness of nations; I have named this in a paper with Dr Mathis Wackernagel from the Global Footprint Network: Competitiveness 2.0; second, the unsustainable link between growth and global goods mobility, which will eventually bring our global interconnected markets to collapse.

Competitiveness 2.0

Competitiveness has been at the forefront of the strategy of many countries. This approach suggests that countries should, as the focus of their national strategies, pursue policies that allow their businesses to create high-quality goods to sell at high prices and to embrace productivity growth. This is based on the assumption that the well-being of a country, measured by its GDP, would be improved through creating the most beneficial national and global regulatory frameworks for business growth. It should be a win-win-win for businesses, governments and citizens, as this approach increases the revenues of companies and increases salaries, which in return boosts tax income. Therefore, a country’s competitive advantage enables it to invest in its social structures and build its social capital. But the economic success of recent decades has translated into higher levels of resource consumption that are no longer sustainable. As a result, countries’ efforts to improve their competitive advantage could lead to a race to disaster.

The fundamental reasons for this race to disaster are as follows:

- All life requires ecological resources, including water and biomass for survival. Most industrial societies are still highly dependent on easily accessible fossil energy resources. Increased pressures on these resources can lead to non-linear effects, including price volatility and supply disruption, with potentially severe shocks for all participants in the global economy.

- The current metrics for competitiveness and economic performance largely ignore the resource dimension, and its potentially non-linear dynamic ignited by supply gaps. While the global market will be able to smooth over local supply gaps initially through trade, all of the participants in the global market will be exposed to global shortages simultaneously. Such potential system shocks may be accelerated, since many nations with critical resources will focus on securing domestic demand before serving the global market.

In the face of this “race-to-disaster” dynamic, there is a profound and urgent need to find answers to the following questions:

- What does it take for governments to appreciate the economic significance of their resource dependence in the context of the current dynamic?

- Considering the pressure of the resource dependence on countries’ competitiveness and social stability, and the potential endangerment of the country’s survival, what are the opportunities for governments to aggressively manage their resource dependence?

- What competitiveness plans do they have in place to succeed in a resource-constrained world?

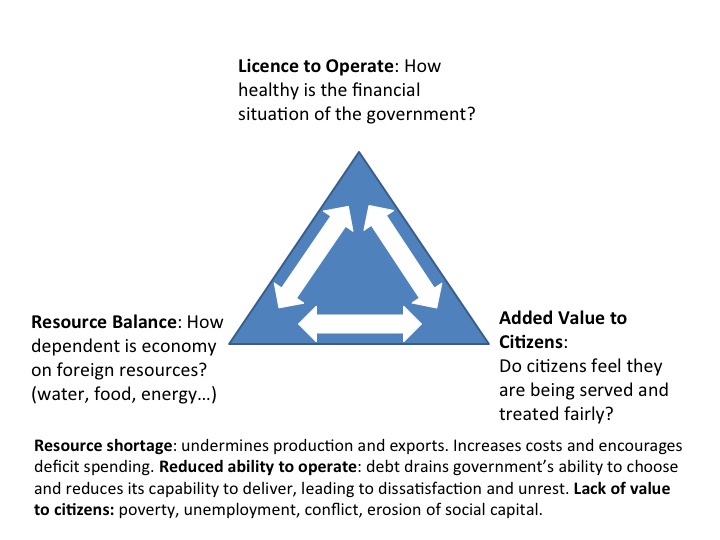

The idea is simple. In a time of growing resource constraints, we need to update national competitiveness strategies. While the elements of traditional competitiveness still hold, it has become clear to many that one key element - national debt - is starting to overshadow other components and needs far more attention. We call this realization "Competitiveness 1.5". But the debt crisis is merely a symptom of a larger structural problem: the fact that resource dependencies and the associated costs and disruption are becoming the key drivers of economic success. In the past, it was rational to ignore them, since they were a declining cost-factor. This calls for "Competitiveness 2.0", which highlights three key elements of the puzzle:

Sustainable Mobility of Goods

In recent decades, the world has become increasingly interconnected. Globalization has permeated all aspects of our lives. This shows us that the process of globalization is not something that will be stopped and even less reversed. We also need to understand that mobility at the global level is the crucial fundament and the framework of globalization, almost like the blood vessels are the crucial fundament and framework of the human body. When we analyze the growth in the movement of goods compared to GDP growth, and if we put this in comparison to the environmental effects of transport, we can foresee the increasing and accelerating negative effect of global mobility on the environment and, hence, see a real risk for the sustainability of the fundaments of globalization.

Given that we have already accepted that globalization is a process that will continue, we need to monitor the future evolution of global mobility and - through analysis and debate - create an awareness that there is a crucial need to change the modal split of global mobility from modes with a high negative effect on the environment and which also have important limitations in their scalability (for example, truck traffic), to modes that are much more scalable, predictable and have less effect on the environment (for example, rail).

Such an evolution can only happen based on commonly-shared and agreed facts. Hence, as a first step, there is a need for a diagnosis tool that allows better understanding and analysis of these dynamics and that helps governments and other stakeholders in the realm of transportation of goods to take the right decisions.

If we wish to better understand today’s situation and its evolution, which has brought us here, and the possible future changes that can be applied to global mobility, we need to look at:

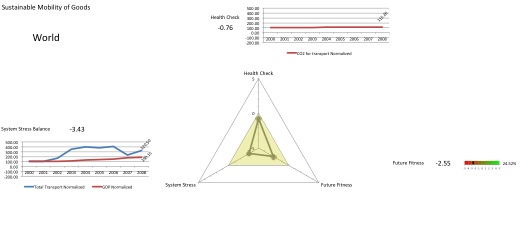

- The dependency of the transport of goods on the evolution of GDP: this shows the increased stress a country will put on its transportation system when attempting to grow its GDP. The more a country depends on transport for its GDP, the quicker it will need to increase the transport infrastructure and the more it will contribute to clogging the global transport system. We call this element the System Stress Balance, and it measures transport growth (in ton-km) versus GDP growth.

- The emission of CO2 due to the transport of goods: this shows the direct effect of transport on the environment. We call this the Health Check as it shows directly how strong and how bad the effects of transportation for any country are on the overall environmental health of our planet.

- When we want to understand the decisions that have been taken to influence today’s use of transport, we need to look at the investments and maintenance for transport modalities like rail, road, waterways and air. When we compare these modalities, we can see that rail and water have, already today, big opportunities for reducing the overall effect of transport on the environment (electrified trains, highly compacted transport) and also the stress on the system (highly compacted transport). Hence, with this measure, we will compare the level of investment and maintenance in these transport modalities compared to road and air. We call this measure Future Fitness, as it expresses the future capability for reducing system stress and environmental effects.

To illustrate the urgency of this discussion on the limits of growth, let me just present the worldwide situation of global goods mobility:

In conclusion, we need to understand that we have to include a pre-occupation with sustainability in every decision we make. Even more so, when we talk about creating the infrastructure for our needs of tomorrow, we will need to have a commonly accepted definition of what a sustainable infrastructure needs as qualities and features.

How to Move Forward

When discussing how to move forward and reconfigure growth to make it more sustainable, we have to understand that this is not about good or bad, but about a sustainable (that is something we can live with, which ensures the long-term maintenance of well-being) balance between economic, ecological and social pre-occupations. This also needs to include a precautionary approach to avoid major negative effects on the economy, the environment or society.

This implies that we need to look at all these challenges holistically. No decisions can be based solely on financial criteria, on environmental criteria or on social criteria; even more so, no decision can be treated as a simple confrontation between economic, ecological and social challenges. Decisions need to be taken based on the best possible balance between all these domains and at the same time ensuring that all negative effects are avoided as much as possible. This also implies that we need a better understanding of all trade-offs and the real implications and, hence, apply the level of precaution necessary. Past experiences have shown that in too many instances we have, by solving one problem, created problems in other domains. For example, when dealing with debt by applying austerity measures, we can see how such measures have a much greater effect on the poor and, hence, create social deprivation, which will in turn also effect tax income and social costs; and, hence, further increase indebtedness. Too often, by trying to solve one issue we create new problems, and, hence, start a vicious cycle that will undermine well-balanced sustainable development.

The Need for a Holistic Approach

We need to learn to look more holistically at the challenges ahead and to integrate the concerns of the economy, the environment and society. Only through this approach will growth be sustainable and have a limited negative effect. This is also just a simple recognition that the world is one system, and any successful solution has to address the world as one and not as number of distinct systems that are not inter-connected. Our capacity to approach the world in a holistic manner can be learned and exercised and this is best done through system thinking (as presented by Peter Senge in his book The Fifth Discipline, 1990). This approach of system thinking has been also presented as the “cornerstone” of a learning organization. Today, the world needs to become a learning organization to find the most successful ways to address the future challenges and, finally, to discontinue the old approaches and behaviors that have abundantly shown how unsuccessful they are.

In conclusion, we do not need a revolution and a total new start, but we need better integration of all of the different challenges in all our decisions and, hence, avoid all the unexpected negative side-effects we have witnessed over and over again in recent years. We also need to overcome our old ways of dealing with the challenges of the commons, such as our environment, as we need to learn that over-use is not without consequence and, hence, we need to find a balance on how we use different resources as this is crucial for our survival and well-being. Hence, we need to realize that a well-understood sustainable approach is necessary and will allow for growth with highly reduced negative side-effects.

Comments

You need to be logged in to add comments. Login